- Rare earths are by no means scarce, but their refining is a capital-intensive and “dirty” process

- Magnetic/electronic properties are what make them critical – in both military and civilian fields

- Amid heightening geopolitical tensions, China’s dominance of supply has become a clear concern

Amid the fast-evolving global geopolitical landscape, with a focus both on securing supply chains and boosting defence capabilities, rare earths are gaining in importance – and investor interest. What exactly are they, why are they critical, are they truly so rare, and can China’s dominance be challenged: these are the questions that we intend to address in this month’s editorial.

To begin with the basics, rare earths comprise a set of 17 elements, 15 having atomic numbers that range from 57 through 70, plus Scandium (21) and Yttrium (39). They are not to be confused with the so-called list of “critical materials”, established by both US and EU authorities on the basis of economic and national security importance, a list which includes the likes of aluminium, copper, nickel or silicon.

Amongst rare earths, the differentiating factor is not chemical properties – they are virtually inseparable on that count – but electronic and magnetic properties. Which in turn makes each of them a critical component of specific technological applications, particularly in currently strategic fields such as the military and energy transition. Take the F-35 fighter jet for instance: it contains over 400 kg of rare earths, used in weapons targeting, lasers, flight control, etc. or electric vehicles and wind turbines, which rely on very powerful and heat-resistant rare earth magnets.

Although termed “rare”, these 17 elements are actually relatively plentiful in the Earth’s crust, across all regions of the globe. They are not always easy to access, however, and their concentrations, while variable, tend to be very low meaning that enormous amounts of raw ore must be processed in order to produce them. Such refining is very expensive, energy-intensive and highly polluting, which explains why China has progressively supplanted the US as the main producer. In fact, so long as the world order was stable, such a Ricardian allocation of production made perfect economic sense.

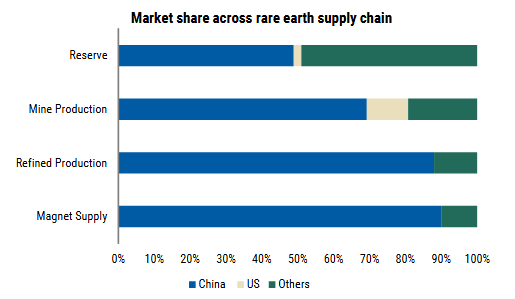

With that backdrop of course now changing, other nations are increasingly uncomfortable with China’s near full control of rare earths (55% of reserves, 70% of mining output and 85% of processing capacity according to the US Geological Survey). The fact that Chinese authorities are using rare earth exports as leverage within trade negotiations, having notably enforced certain export restrictions as a retaliatory measure for higher US tariffs and semiconductor shipment bans, is only reinforcing Western efforts to regain a form of supply independence.

From an investment perspective, the massive capex requirements involved in rare earth production, making the business model uneconomical absent state and/or corporate guarantees, used to be a clear deterrent. Such support is now happening though, as evidenced by the multibillion public-private partnership announced in July between MP materials and the US Department of Defense – aiming to “catalyze domestic production”. Or Japanese investments (via the JOGMEC government agency and Sojitz trading house) in Australian miner Lynas Rare Earths, in which the Aegis fund also owns a stake.

To conclude, rare earths are somewhat of a misnomer, and the current Chinese “monopoly” looks set to erode over time. But this will be a gradual and lengthy process. Alternative technologies are meanwhile also being pursued, with quite some promise, but they too are a long-term perspective. What is certain is that, for nations across the globe, achieving sufficient and safe supply of rare earths is a prerequisite to developing high-end military capabilities and managing the energy transition – two absolute current priorities.

Written by Roberto Magnatantini, Senior Equity Portfolio Manager

A Fed rate cut is needed to cement the soft landing

- One all-time high chasing another, fuelled by a supportive macro backdrop

- Beware of overconfidence though, as it is weakening the favourable Goldilocks’ regime…

- …. and driving a growing asymmetry in risk assets, with decreasing odds of a large rally

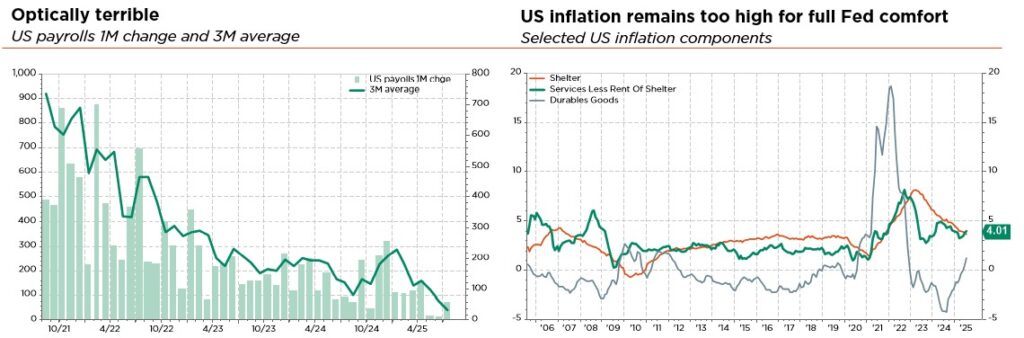

Despite President Trump’s ongoing gesticulations about tariffs, Fed monetary policy or geopolitics, the Goldilocks’ regime has continued throughout the summer, helped by tailwinds from a strong US earnings season and dovish Fed expectations. This has led to further risk premium compression and a volatility reset. Assuming favourable macro conditions, this backdrop may extend further but there is a latent risk of unwinds in the event of negative growth surprises, stubbornly high inflation or rate shocks.

What could go wrong? “Many things” could obviously be the short answer, with the underlying story remaining basically unchanged. Either US growth peters out faster and more significantly than expected and the Fed does finally appear to have fallen behind the curve, or inflation comes back to the forefront, precluding pre-emptive monetary easing over the next few months. In the meantime, a third endogenous risk is emerging: investor overconfidence in the never-ending Goldilocks backdrop, which is pushing asset valuations to extreme levels. Indeed, investors are likely getting ahead of themselves by taking a September rate cut for granted, such a move also being necessary to cement the soft-landing narrative. Considering the current complacency, the lofty valuations, as well as the narrow market breadth, a whole series of potential sparks, in the form of surprising enough economic data releases, could thus lead to a (healthy) short-term correction.

To sum up, the backdrop remains supportive but is expected to become more fragile – especially in the US – going forward, while valuations of risk assets are stretched and even historically expensive in some specific areas, as investor overconfidence veers towards greed.

As a result, and based on the history of low-volatility regimes, we see a growing asymmetry in risk assets: the odds of a large rally are decreasing, because such rallies tend to occur during recoveries with inexpensive valuations (when excess pessimism dominates), but the probability of a drawdown has increased recently due to this combination of elevated credit and equity valuations, and a weakening business cycle, especially in the US.

In fact, the macro backdrop now seems more supportive in Europe, with economic growth expected to pick up, inflation risks already under control and a more straightforward ECB easing cycle to date. Unfortunately, there are two caveats to this assertion. First, the toxic mix of political instability and a public deficit getting out of control in France represents a serious threat for the whole euro area financial stability. And secondly, a major economic or financial shock in the US would – in the eyes of global investors – likely outweigh and drag down the nascent optimism regarding a revival of the European economy and markets.

No changes have thus been implemented at the portfolio level. We are maintaining our overall neutral stance on both equity and fixed income. This balanced positioning and well-diversified allocation reflects our cautiousness in assessing the wide range of potential outcomes. It should allow portfolios to benefit from expected positive, but contained, returns in most asset classes in the near term, mitigating the usual abrupt but inevitable bumps due to sector rotation, while maintaining sufficient flexibility to adapt to evolving conditions along the journey. That said, in an opportunistic manner, we may embark tactical protections – as is indeed the case currently. We continue to view portfolio diversification as a key requirement, within both equities (regions, sectors, styles and company size) and bonds (regions, maturity buckets, sectors and credit risks), but also via exposure to gold, which is still preferred to government bond duration (absent a severe recession scenario) as a broad safe haven in various risk-off scenarios.

Written by Fabrizio Quirighetti, CIO, Head of multi-asset and fixed income strategies

External sources include: LSEG Datastream, Bloomberg, FactSet, Morgan Stanley.