- Supply chain to be durably impacted by the Covid lessons, the energy transition and geopolitical tensions

- Multinationals are striving to nearshore production, bringing it closer to customers

- Various benefits can be expected: less transport costs, faster response, better ESG profile…

Chinese authorities seem to be finally putting an end to their strict zero Covid policy. But the pandemic, with its extended periods of factory lockdowns and port closures in China, will leave a lasting mark on supply chains. Starting in March 2020, populations and company managements alike learnt in the hard way that access to critical semiconductor or medical devices could be halted for weeks on end. Mounting geopolitical tensions and the emergence of a multipolar World have since only served to heighten supply uncertainty, prompting the widespread rethinking of “just-in-time” production. Resiliency (termed by some as “just-in-case”) is the new mantra, arguing for manufacturing facilities that sit closer to end markets.

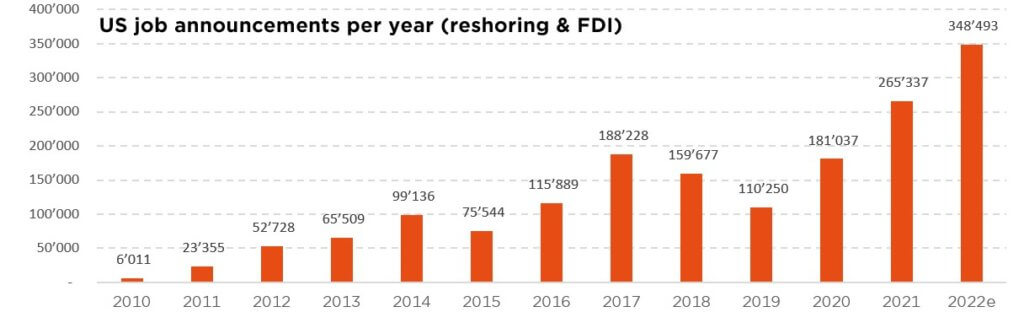

Indeed, a recent ABB survey suggests that a full 70% of US manufacturing companies intend to set up, or relocate, their productive capacity closer to home/customers. Such nearshoring rises various challenges but also bring a number of benefits, beyond just the lesser dependence on Far Eastern factories. Companies can save on expensive – and very volatile – freight costs, ditto for duty fees and tariffs. They also reduce their response time, are better able to adapt to local regulations and face less currency risk. Not to mention potential ESG brownie points like on the child labour or CO2 emission fronts.

All these are factors that “push” companies to nearshore their production. But there are also a number of “pull” factors that warrant mentioning, and that make some countries better positioned than others to harbour these relocated manufacturing facilities. Geographic location of course springs first to mind, meaning Latin America for the US market or Northern Africa/Eastern Europe for the old continent. Second on the list is the existence of free trade agreements, which notably argues in favour of Mexico (courtesy of its long-held NAFTA tie to the US and Canada). The quality of a country’s manufacturing base is a third key factor, followed by macroeconomic and political stability. Last but not least is the labour force that is at hand: it needs to be both sufficiently qualified and comparatively cheap. Adding up all these criteria points to the aforementioned Mexico, alongside Morocco, Turkey and Eastern Europe.

Examples of companies, within these countries, that are capitalising on the nearshoring trend are manifold and cover a broad range of industries. Take for instance Global Foundries in the semiconductor space, which has just completed its first full calendar year as a publicly traded company. Figuring among the world’s leading chip manufacturers, it stands top when it comes to its global manufacturing footprint without any presence in China or Taiwan. Energean is smaller but it still stands to play a role in providing gas to Europe now that the ties with Russia have been severed. BBVA, the 3d largest bank in Spain, is the largest lender in Mexico and also holds strong position in Turkey. In the automotive space, Italy’s Brembo just announced doubling its capacity in Mexico. Railroad companies such as Burlington Northern SantaFe (owned by Berkshire Hathaway), Kansas City Southern or Union Pacific should clearly also benefit from that trend. And these are but a few examples…

All told, nearshoring offers an alternative to both the extreme globalisation of the past two decades and the increasingly protectionist trends of the past few years. A middle route, reasonable and reasoned, that could work to the advantage of workers and consumers alike – as well as astute investors.

Written by Roberto Magnatantini, Lead Portfolio Manager of DECALIA Silver Generation & DECALIA Eternity

Less growth, sticky inflation & higher-for-longer rates

Global economic growth will continue to slow as we enter 2023. The US may manage a soft landing on the back of a rebound in real personal income – thanks to wage growth that is likely to remain buoyant amid decelerating inflation. Interest rate sensitive sectors, such as housing, will weigh on overall growth, but in a manageable way. For the second half of 2023, the US trajectory looks more uncertain as the full impact of financial tightening will bite, the labour market will be less supportive and the pullback in inflation may already have ended.

In Europe, a recession seems inevitable. The Euro Area will continue to face a supply shock, in the form of an energy crisis, with fiscal support delaying the necessary downward adjustment in demand and thus forcing the ECB to pursue its rather unusual bold and swift tightening, paying little attention to growth. In this context, the war in Ukraine, as well as global geopolitics risks, still represent both a drag on overall economic activity and a source of unhealthy inflationary pressures.

Last but not least, China will remain an outlier with its growth expected to rebound as Covid restrictions are eased – even if the trajectory may prove bumpy – and economic policies remain supportive (no rate hikes on the horizon). Still, the structural macro backdrop remains challenging as the country tries to escape the “middle income trap”, with an already ageing population. Finally, it is worth noting that growth in EM economies will also slow in 2023, albeit more modestly than in DM, and with some usual divergences among this heterogenous group.

Inflationary pressures will recede during the first part of 2023, on the back of more favourable base effects, the recent drop in energy and commodity prices, easing supply chains and slower growth. There is, however, little clarity as to the extent and speed of this decline. Moreover, inflation could tend to prove structurally higher than in prior decades owing, amongst others, to a more fragmented world, ageing demographics, the ongoing energy transition and more supportive fiscal policies. As such, despite recessionary concerns, inflation still represents a major risk for markets in the sense that overly high prints will certainly lead to further monetary tightening and a delayed, but more severe, recession.

The major DM central banks are thus likely to continue hiking rates through spring at least. The Fed will slow its hiking pace, then mark a pause, so as to assess the full impact of higher rates on economic activity. How fast and by how much will inflation recede? How severe a recession? These unknowns – as of today – obviously hold the key to the level and timing of terminal rates, as well as the odds for potential cuts in H2 2023. Since we expect the US economy to manage a moderate – albeit long and bumpy – landing, expectations of a dovish Fed pivot still do not feel right to us.

We thus see no respite for investors. Near-term visibility remains is low with an alternation of sporadic bear market rallies on the one hand, and pullbacks induced by spiking bond yields on the other, lying ahead. Admittedly, our base case still presumes a soft-landing but the time sequence of receding inflation and slowing growth (recession) matters more today, leaving global equity markets at the mercy of central bank decisions. In particular, we believe the latter’s “higher for longer rates” stance, suggesting the tightening cycle is far from over, calls for still bumpy global financial markets. As such, we retain our cautious tactical stance on both equities and bonds.

Written by Fabrizio Quirighetti, CIO, Head of multi-asset and fixed income strategies