- Western countries, but also China, are battling with ageing populations

- Slower growth, the cost of healthcare and pension funding are but some of the issues

- What if the current storms were to herald a new socio-political and economic era?

If deciphering the economic cycle has never been this difficult, it is certainly because other, more structural forces are currently at play. Beyond complicating the interpretation of economic reports, the Covid pandemic and subsequent war in Ukraine have also served to accelerate some underlying trends. It is quite possible that we stand today on the threshold of a new socio-political and economic era, largely because of demographic evolutions.

To come back to the very foundations of economic theory, a nation’s potential growth is determined by two factors: population growth and productivity gains. Many countries are, however, today experiencing demographic declines due to very low fertility rates.

The example that immediately springs to mind is Japan. During 2022 alone, the country lost 800,000 residents. And a report published this year by the Ministry of Health and Welfare points to a potential 30% drop in Japan’s population by 2070. With one in three citizens currently over 65, the Japanese Prime Minister has openly expressed concern about the country’s ability to “continue to function as a society”. Indeed, ageing demographics means a shrinking workforce and, as a result, lower production/consumption, exploding healthcare costs, growing indebtedness, falling property prices, a more fragile pension system, staff shortages…

Its big neighbour, China, is headed in the same direction, with 850,000 fewer residents in 2022 and a one-child policy that, although abandoned by authorities, remains deeply entrenched. “Zero Covid” measures undoubtedly aggravated the situation by weighing on economic growth and adding to the prevailing uncertainty. What makes China’s case particularly problematic is that its population will become “old” before it can get “rich”.

Conversely, countries with rapidly growing populations, such as India, Turkey and a good part of Africa, are posting high GDP growth rates. Which, incidentally, does not necessarily ensure superior stock market performance or financial success! Other variables matter of course too: economic policies, education, business conditions or central bank independence/credibility, to name but a few.

While immigration may seem a solution for ageing countries, it is clearly no panacea, to the extent that it removes vital forces from the countries of origin and causes integration issues in the countries of destination – a sad reality that fills the media almost daily. Each country has its own approach to immigration: historically strict Japan is today toying with more lenient policies, while Hungary has clearly made the choice of an “anti-migrant natalism”.

Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan’s book “The Great Demographic Reversal: Ageing Societies, Waning Inequality, and an Inflation Revival”, published in 2020, is a reference with regards to this fascinating subject, and its multiple ramifications. As the title suggests, the authors predict a reversal of the past three decades’ trends, with a resurgence of inflation and rising interest rates.

Recent history has tended to confirm these predictions – let us hope that the same will go for the asserted eventual reduction in inequality. Today’s storms might then give way to better times down the road. For the sake of the younger generations, we can only hope such a scenario comes true. And that the older ones will live long enough and in good health to experience it themselves…

Written by Fabrizio Quirighetti, CIO, Head of multi-asset and fixed income strategies

Near-term resilience, persistent challenges

- Mixed macro salad – with extra oil and a pinch of salty higher yields

- “Higher for longer” rates are gradually becoming a major overhang for equities

- Valuation levels leave little room for error, thus keeping us tactically prudent

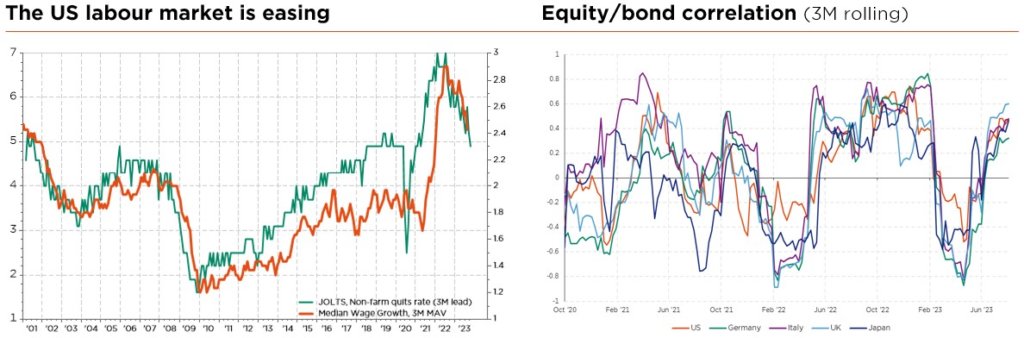

September saw global economies continue to walk a remarkably fine line between inflation, growth and policy, supporting the odds of a soft-landing scenario – despite the rebound in oil prices and backup in bond yields. Albeit slowing, economic activity remains resilient (with China still the wildcard), disinflation is well underway, destocking trends have peaked, the rate hiking cycle is coming to an end, and labour markets are now reassuringly easing somewhat. Admittedly, trends in Europe are more subdued and China will struggle to implement bazooka stimulus measures this time round, but a severe near-term global recession can be ruled out in our view. Even as credit tightening and monetary policy are starting to bite, major central banks have again made clear that interest rates will stay “higher for longer” this cycle, not least because of rising energy prices, thus forcing an adjustment in the valuation frameworks for the major asset classes.

Our macro scenario still foresees a slowdown in growth and lower inflation (but remaining above central bank targets for the foreseeable future) leading to hawkish “hold” monetary policies. As such, with no major correction in risky asset markets – driving valuation back to more attractive levels and forcing central banks to adopt a more dovish stance – expected anytime soon, we anticipate a continuation of the tug of war between restrictive monetary policy on the one hand, and unusually resilient growth/sticky inflation on the other… until something eventually breaks.

While some of the excessive pessimism regarding growth has admittedly dissipated, latent risks persist (energy prices, China’s anemic recovery, growing debt supply, distress risks or deepening geopolitical & socio-economic fragmentation). Of all these, it is the “higher for longer” rates, on the back of sticky inflation and debt (over)supply concerns, that are gradually becoming a major overhang for equities, as illustrated by the current positive correlation between bond and equity returns.

Furthermore, sentiment and positioning indicators are no longer supportive, while global equity markets, and especially the US, still look expensive according to most metrics, seriously impairing equities’ relative appeal in today’s higher (real) yields environment. Looking beneath the index surface, multiples may not all look as stretched, with attractive pockets of value still to be found in selective high-quality equities across other regions or sectors, but current valuation levels leave little room for error, thus keeping us tactically prudent in terms of overall asset allocation.

As a result, we have made no changes to our regional preferences, maintaining our slight underweight of Europe alongside our slight overweight of US and Japan, and mixed views on emerging markets. On a more granular level, we have nonetheless adjusted our sector allocation, taking some profits on IT following this year’s rally. This change is consistent with our earlier view that market breadth should continue to widen, spurring a further catch-up for some of this year’s high-quality but less growthy (i.e. more value) laggards.

While sovereign bond duration may help mitigate possible equity losses related to an earnings recession, we still doubt its buffer potential in a context of sticky inflation, “hawkish hold” policies and government debt wave. That said, with long rates having continued to edge higher, reaching record levels since 2007, we now consider them fairly valued and thus recently decided to add back some duration (remaining overall slightly underweight given the more appealing higher and uncorrelated cash returns).

No change elsewhere: we keep our slight overweight of gold and slight underweight of other materials, while still anticipating a lack of direction for major currencies crosses in the next few months (the dollar may get a touch stronger near-term, and the Swiss franc somewhat weaker, but we do not expect these trends to last).

Written by Fabrizio Quirighetti, CIO, Head of multi-asset and fixed income strategies

External sources include: Refinitiv Datastream, Bloomberg, FactSet, OECD Data