Reji Vettasseri, Lead Portfolio Manager of DECALIA Private Credit Strategies

- The recent First Brands bankruptcy had little to do with private debt

- Private credit is outperforming traditional credit including on default rates

- Private credit creates less systemic risk than the banking system

Superheroes or villains?

Private lenders might seem to think of themselves as nothing short of financial superheroes – offering hope and smart capital to the world’s forgotten borrowers, and drawing strength from elevated base rates to deliver supercharged returns. But every time a major default hits the headlines, they get recast as Wall Street’s newest villains: “shadow bankers” (an alias worthy of antagonists in a third-rate Marvel spinoff). The truth is more nuanced than can be expressed in simple comic book colours.

This is highlighted by overreactions to two US bankruptcies (Tricolor and First Brands). Some suggest these cases are representative of broader risks, even systemic risks, related to private debt. In fact, they are neither representative (recent private credit returns are strong and current default rates manageable), nor could they be systemic (the siloed structure of the private credit market prevents this), nor even are they to do with private debt (traditional lenders were the main funders of both firms).

However, especially amidst volatile market and macro conditions, beware of any lender with a Superman complex. A feeling of invulnerability is a weakness in and of itself. Stories like First Brands do highlight real issues to look out for: commodification leading to loosening standards in certain segments, the bad side of financial engineering and the risk of under-diversification. Fortunately, these pitfalls are largely manager or strategy specific and can be avoided with good selection.

Busting the First Brands Myths

1. Not Private Credit

In Sep-25, US auto lender Tricolor collapsed, with liabilities in the $1bn to $10bn range according to in its Chapter 7 filings. Weeks later Ohio-based auto parts supplier First Brands followed suit, with $12bn of debt outstanding1. The failures were not just big, they were also murky. Although no wrongdoing is proven or admitted, several lenders have publicly accused both companies of fraud, including “double pledging” of assets as security for multiple loans2,3. Which lenders got caught up in all this?

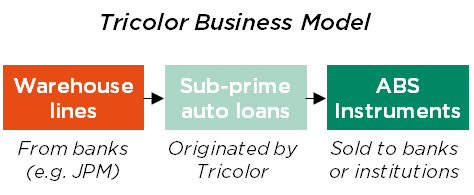

Tricolor offered “sub-prime” loans to consumers who had limited credit history but wanted to buy a car. Its own money came from “warehouse lines” provided by traditional banks (including JP Morgan, Barclays and Fifth Third) and from selling on pools of its loans to asset-backed securitisation (ABS) vehicles, which are SPVs that issue traded (i.e. public or semi-public) debt4.

Source: Financial Times5

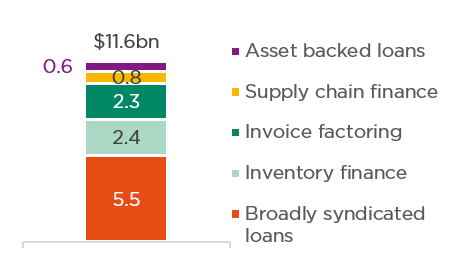

First Brands raised debt for an M&A spree. Most was broadly syndicated loans (BSLs) – traditional leveraged loans, syndicated by investment banks primarily to commercial banks and CLOs (another type of securitisation SPV). It also took out a complex array of asset-backed loans secured against every sliver of its working capital. These were mostly provided by banks, trade finance companies and hedge funds5.

If you are confused by the complexity, so were the lenders, who lost track of credit fundamentals. But, within the vast cast of characters, private credit funds were only bit players. Jeffries’ and UBS’ investment management arms did respectively have $715m and c.$500m of exposure to First Brands asset-backed debt6,7. But while a portion was private credit, much was in hedge funds with more liquid strategies. Business development corporations (BDCs), had $229m of exposure to First Brands8. These US crossover vehicles do offer private debt, but here were exposed via pockets devoted to conventional BSLs.

Less than 10% of the total debt in the two situations was private credit, even under a loose definition of the term. The bulk was provided by banks and traditional participants in syndications and the securitisation market.

Indeed, we like private lenders because they try to avoid syndications with pre-set terms and borrower-managed access to information. Instead, they seek to be the key players in deals that are bilaterally negotiated after deep due diligence, where they have enhanced monitoring rights and control over enforcement if things go wrong.

Not only were these elements missing in First Brands and Tricolor, their absence was precisely why things went wrong. Atomised capital structures mean no individual lender has full visibility or control. A concentrated, private lending group might have managed better. Private debt did not cause the issues; perhaps it could have been the cure.

2. Not Representative

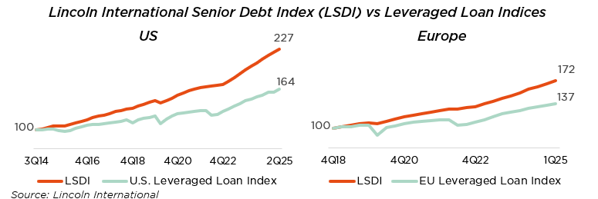

Overall private debt performance is on a strong run. As shown below, comparing Lincoln International’s private debt return indices against leveraged loan benchmarks9, not only has private credit outperformed, it has done so by a widening margin and with less volatility. Other datasets (e.g. Houlihan Lokey’s indices10) show similar results, but also focus on senior direct lending – the most competitive market segment. Our experience is that the trend is even more pronounced for specialised credit.

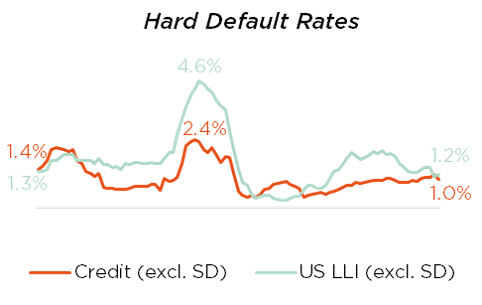

On the other hand, the S&P data below do show that “hard” defaults, such as bankruptcies or missed payments have been slowly ticking up since 2022, when rising inflation, higher financing costs and weak macro began to weigh on borrowers11. This does matter but needs context. The current hard default rate of 1% is still below historical levels seen in Covid or even in 2017/18. Moreover private credit has been faring better than traditional leveraged loans.

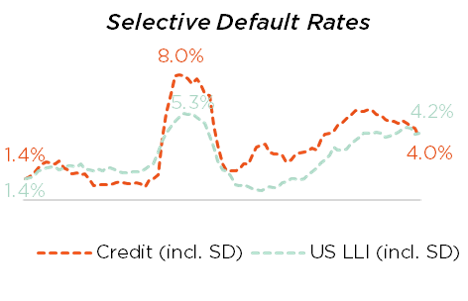

Some suggest problems are being swept under the carpet by private credit tolerating “selective” defaults, e.g. payment holidays when borrowers can capitalise interest rather than pay cash. At c.4% the selective default rate is four times higher than the hard rate.

However, a closer look at the data shows that the selective default rate actually declined since mid-2023 for private credit. It is now lower than for leveraged loans, where the rate picked up later but is still rising. The best explanation is that, far from kicking the can down the road, when problems loomed, actively managed private debt was better at agreeing consensual strategies to relieve short term pressure on borrowers and to plot a sustainable path forward. It is traditional credit that may only be facing up to problems now.

We are watching closely. A mild default cycle is unfolding and may well worsen. But, so far, default rates seem within tolerance levels and normal for a period with choppy macro conditions, rather than symptomatic of loose underwriting. Furthermore, private debt looks more resilient than other credit asset classes.

3. Not Systemic

The scariest sounding charge against the “shadow bankers” is that of systemic risk. It is also the easiest to deal with.

In a banking crisis, defaults in one unit of a bank brings down an institution and then affects its myriad counterparties. Such contagion is unlikely in private credit. If a fund hits trouble, it will be bad for its LPs. But long term assets are matched with long term funding, so there can be no run on the bank. And, as risk sit in siloed funds, rather than on a single balance sheet, issues should be limited to a vehicle, rather than bringing down a manager or the system.

When the IMF or central banks worry about “private debt”, there may be a definitional confusion. They often mean all non-bank lenders: targets include unregulated corporates like Tricolor or the alphabet soup of acronymed securitisation SPVs we met earlier12.

The Risks of Feeling Invulnerable

Although some critiques feel like noise, the biggest problem with them is that they can drown out the real issues:

1. Commodification

Private credit used to claim to be a niche strategy that could cherry pick the very best deals in a much bigger debt market. But today it has $1.7trn in AUM, and is the dominant source of capital in areas such as LBO financing13.

Alpha does exist in private credit, but increasingly it belongs less to the asset class as a whole and more to individual strategies and managers.

As First Brands and Tricolor show, large cap borrowers can take their pick from a wide array of financing options. Too much competition lead to a race to the bottom not only on returns but also on risk management. We prefer situations where private credit lenders with a more specialised focus find off-market deals or offer something truly differentiated.

2. Financialisaton

You cannot carve a turkey to get a filet mignon. It remains a turkey. Similarly you cannot slice and dice the debt of a failing company and find a good credit.

We like bespoke financings that solve real problems. We do not like structured finance when all it does is parcel out exposure in ways that obscure risks. First Brands and Tricolor had overcomplex capital structures, and due diligence may have been missed amidst an obsession with financial engineering.

3. Under-diversification

Although private credit was a small part of the First Brands story, the FT reports that one UBS fund still had 30% of its portfolio exposed to the situation. Concentration limits should stop this. But here, while direct exposure to First Brands was only 9.1%, the fund also had a 21.4% indirect exposure via invoices owed to First Brands by its customers. This all highlights that diversification requires both a high number of assets and a low level of shared risks.

Even in fund portfolios, issues arise if allocating to multiple GPs focussed on the same segment or involved in the same club deals. Investors should assess their full set of options, including varied corporate and asset-backed strategies, across a range of geographies.

With Great Power Comes…

Private credit is a larger asset class than it used to be. That makes it a bigger target for those looking for a new financial bogeyman. But, even if some criticism is unfair, as they say in the Spiderman comics, “with great power comes great responsibility”.

The responsibility for GPs is to stay disciplined on risk management and focussed on situations where they truly add value. All claim to do so, but the responsibility for LPs is to see behind their masks and select only the good guys who remain true to themselves.

Copyright © 2025 by DECALIA SA. All rights reserved. This report may not be displayed, reproduced, distributed, transmitted, or used to create derivative works in any form, in whole or in portion, by any means, without written permission from DECALIA SA.

This material is intended for informational purposes only and should not be construed as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument, or as a contractual document. The information provided herein is not intended to constitute legal, tax, or accounting advice and may not be suitable for all investors. The market valuations, terms, and calculations contained herein are estimates only and are subject to change without notice. The information provided is believed to be reliable; however DECALIA SA does not guarantee its completeness or accuracy. Past performance is not an indicator of future results.

Sources:

1 Tricolor and First Brands Chapter 7 Filings (PACER)

3 Bloomberg, “Tricolor Trustee is Probing Fraud’”, 3-Oct-25

3 Financial Times, “First Brands Formally Accused of Massive Fraund”, 31-Oct-25

4 Financial Times, “JPMorgan and Fifth Third face losses tied to collapsed subprime car lender”, 31-Oct-25

5 Bloomberg, “The Secretive First Brands Founder His $12bn Debt and the Future of Private Credit”, 15-Oct-25

6 Reuters, “Jefferies discloses fund exposure to bankrupt First Brands”, 8-Oct-25

7 Reuters, “UBS examines hit from $500 million First Brands exposure”, 8-Oct-25

8 Private Debt Investor, “First Brands Bankruptcy Prompts Questions Over Private Credit Exposure”, 15-Oct-25

9 Lincoln International, Lincoln Senior Debt Index Q2 25 vs. Morningstar LTSA US Leveraged Loan 100 Index and ELLI

10 Houlihan Lokey, Private Performing Credit Index

11 S&P Global, Private Credit: The Rising Defaults”, 4-Aug-25

12 IMF, “Growth of Nonbanks is Revealing New Financial Stability Risks”, 14-Oct-25

13 Preqin

14 Financial Times, “First Brands Pain Hits UBS”, 7-Oct-25

All analysis based on latest available data as of 1 November 2025